Anyone can write a standard history of our community using the same old measurements of time—political elections, wars, and, in the case of Rocket City, even moonshots become the foundation for which we mark the passage of time.

But what if we stepped off that historical bedrock that began to form during our third-grade Huntsville history class, and instead, we traced the flow of water through our collective past?

How different would the H2O history of Huntsville look?

The H2O History of Huntsville

Water has been essential to life since the first human stepped into the Tennessee River Valley thousands of years ago. Regardless of age, class, gender, or race, water has quenched our thirst, provided sustenance, watered our crops, moved our products, powered our homes, served our spiritual needs, and been recreated on.

Long before John Hunt illegally squatted on a piece of land next to a natural spring in 1805, the Cherokee and Chickasaw roamed what now is North Alabama. Aside from using the rivers and streams as watery highways and as a source of food, many of our earliest ancestors started their day by laying in the Tennessee River; infusing their bodies and souls with nameless energy that came from water.

This all changed after John Hunt settled next to what we now call Big Spring in 1805.

Suddenly, a distant America, one that had hugged the Atlantic Coast until after the American Revolution, pushed westward with a manifested destiny that had little regard for those who were already on the land . . . and the water.

Thousands of Americans followed their destiny into the Tennessee River Valley; chasing bountiful land, new cash crops, and the American Dream. They had been infected with what one contemporary newspaperman called “Alabama Fever.”

Alabama Fever swept across the land and brought with it hardworking pioneers, cotton, and a large involuntary group of people, who by law, weren’t even considered to be people. Water mattered more than ever as cotton planters and their slaves tamed the cotton frontier and transformed Huntsville into an inland port that fed the growing ambitions of a new nation.

Cotton became king and Huntsville’s growth reflected this new American royalty. The waters of the Tennessee, Flint, and Paint Rock nourished the land. The princes of cotton, men such as Thomas Fearn and LeRoy Pope, built the Indian Creek Canal using the waters of John Hunt’s Big Spring to float cotton bales to large steamships that then pushed hundreds of bales of white gold to markets in Mobile and New Orleans.

Alabama cotton eventually then made its way to New England to feed the Industrial Revolution of two continents. The same water that had once nourished the souls of the Cherokee and Chickasaw now filled the pocketbooks of American and European merchants, bankers, and industrialists.

But the Civil War and federal military occupation abdicated cotton’s throne in Huntsville and by 1865 cotton was no longer king and slavery, although legally ended, had assumed another name. But sharecroppers needed water just like their royal predecessors. Cotton would continue to dominate the land for another hundred years.

Searching for new opportunities and larger profits, local farmers rebranded the area as the “Watercress Capital of the World” and used watery fields to stake their global claim on the arugula market after the Civil War. Yet, their splash was small and their claim fleeting, and soon Huntsville was looking for something bigger and better.

Since 1805 the waters of Big Spring had nourished a growing town, but by 1905 the same waters were now serving a bustling city growing in all directions. Tracy W. Pratt had arrived, and just like the earliest settlers, he wanted to transform Huntsville and the Tennessee River Valley.

Instead of shipping Alabama cotton to northern factories, Pratt brought northern factories to Huntsville and the surrounding area. Water pipes now stretched from pumphouses in Downtown Huntsville to Lincoln Mill, Lowe Mill, Merrimack Mill, and dozens of other small mills and factories and their surrounding neighborhoods.

The hot fires of industrialism heated the waters enough to create the steam that powered Huntsville into the twentieth century.

Then suddenly it all changed. The happy days of the Jazz Age slipped into the misery of the Great Depression. But once again water came to the rescue in the Tennessee River Valley. In 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Tennessee Valley Authority to help pull a struggling nation out of a financial catastrophe. The TVA harnessed the Tennessee River and created electricity, opportunity, and a new standard of life for those who lived in “Our Valley.”

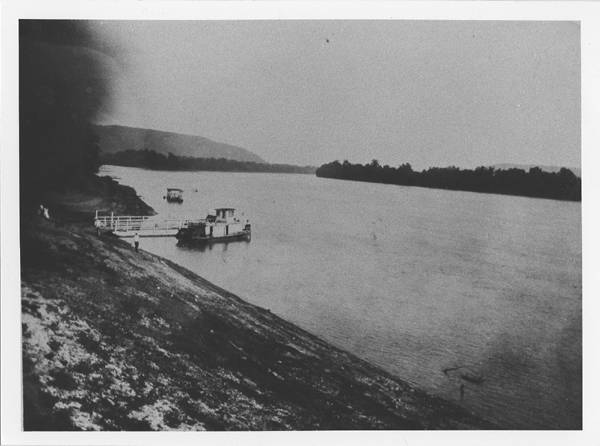

The power of TVA water, cheap land, and an ample workforce brought Huntsville Arsenal to the banks of the Tennessee River as the world went to war in 1941. And although it closed after World War Two, it came back as Redstone Arsenal and Marshall Space Center. Large rocket components could be easily transported on the deep waters of the Tennessee.

Although Big Spring stopped being Huntsville’s main water source in the 1960s, it has become the centerpiece of Downtown Huntsville’s twenty-first century renaissance. The Indian Creek Canal may no longer ship cotton to market but it serves as a wonderful backdrop for many a family picture or leisurely stroll. That local craft beer you enjoy starts with local water . . . the same waters that made Huntsville’s first beer in the 1820s. The TVA continues to power North Alabama with affordable hydro-generated electricity and has created a watery playground for our region.

So next time you take a drink of local water, enjoy a day on the lake, flip on a light switch, enter Gate Nine on the Arsenal, take a picture next to a puffy white cotton field, enjoy Downtown, or walk into Lowe Mill . . . think about how it all got here because now you know the H2O history of our community.

Guest blogger for We Are Huntsville. Are you interested in writing a post for our site? Email katelyn@wearehuntsville.com.

Fantastic history and loved the pictures also. Thank you